The 1976 Copyright Act went into effect on January 1, 1978. The Act provided authors (and some heirs, beneficiaries, and representatives) with the right to terminate prior grants of their copyrights under certain conditions and within specific timeframes.1 Beginning on January 1, 2013, many artists and musicians who transferred their copyright rights after the Act was enacted 35 years ago finally gained the opportunity to terminate those transfers.

The purpose and rationale of the termination provisions was clearly equitable in nature, to allow authors or their heirs a second opportunity to share in the economic success of their works. The House report accompanying the Act explained that the provisions were “needed because of the unequal bargaining position of authors, resulting in part from the impossibility of determining a work’s value until it has been exploited.”2 Further, the Congress that enacted the Act specifically recognized the necessity of “safeguarding authors against unremunerative transfers”3 as justification for its providing authors with the opportunity to subsequently terminate prior transfers.

The termination provisions involve very specific and formulaic timeframes and notification requirements for two types of grants: (1) those made prior to January 1, 1978 (the effective date of the Act), and (2) those executed on or after such date. An overview of both is detailed below. However, despite what was clearly the best intentions of Congress to provide authors and/or their heirs with a second bite of the proverbial apple, an unfortunate oversight on Congress’s part in drafting the Act has created a dilemma that could prove costly for many authors and heirs looking to exercise their termination rights.

The dilemma involves how the Act’s termination provisions apply, if at all, to what have come to be known as “gap works.” Gap works are works that were transferred and/or assigned by an agreement dated before the effective date of the Act (January 1, 1978) but not actually created until on or after January 1, 1978. This “gap dilemma,” unless clarified by Congress, could adversely affect authors by, among other things, stemming a multitude of litigation, which may defeat the purpose of the Act and deter authors from seeking to enforce their reversion rights by making it cost prohibitive to do so.

TERMINATION RIGHTS UNDER 1976 COPYRIGHT ACT

The law relating to the termination of transfers and reversionary rights in connection with copyright grants executed on or after January 1, 1978, is set forth in 17 U.S.C. § 203. The law relating to the termination of transfers and reversionary rights for copyright grants in existence prior to January 1, 1978, is set forth in 17 U.S.C. § 304(c) and (d). Both §§ 203 and 304 vest in authors and/or their heirs a right to terminate their prior grants during a set time period after execution, and are designed to protect authors and to confer on them an additional opportunity to profit from their works.4

Termination of the Grant

Section 203 provides that any exclusive or nonexclusive grant of a transfer of copyright, “executed by the author on or after January 1, 1978, otherwise than by will, is subject to termination.”5 The “[t]ermination of the grant may be effected at any time during a period of five years beginning at the end of thirty-five years from the date of execution of the grant.”6

Section 304(c), on the other hand, provides that the exclusive or nonexclusive grant of a transfer or license of a renewal copyright or any right thereunder, executed before January 1, 1978, otherwise than by will, is subject to termination.7 Under Section 304(c), “[t]ermination of the grant may be effected at any time during a period of five years beginning at the end of fifty-six years from the date copyright was originally secured, or beginning on January 1, 1978, whichever is later.”8 Thus, as opposed to § 203, in which the timeframe is set based on the “date of the execution of the grant,” under § 304 the termination timeframe is set based on “the date [the] copyright was originally secured.”9

Section 304(d) provides another opportunity for authors and/or heirs to terminate a grant made prior to January 1, 1978, which grant was not timely terminated during the window allowed by the 56-year measure set forth in § 304(c).10 Where § 304(c) termination rights have expired on or before the effective date of the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act (October 27, 1998) and the author or owner of the termination rights has not previously exercised any termination rights, the grant may be terminated at any time during a five-year period beginning at the end of 75 years from the date on which the copyright was originally secured.11 The termination of this 20-year extension is subject to all of the other requisites of termination applicable to grants terminated under § 304(c).12

Terminations of grants under both §§ 203 and 304(c) and (d) “may be effected notwithstanding any agreement to the contrary, including an agreement to make a will or to make any future grant.”13 Generally speaking, the only transfers excluded from the termination of grants are for works made for hire and grants made by will.14 Additionally, there are limitations relating to the termination of a grant to the extent such grant included foreign rights,15 which are not terminable, and derivative rights, which, if exercised prior to the termination, can generally continue to be exploited.16

Notice of Termination

Notification Periods

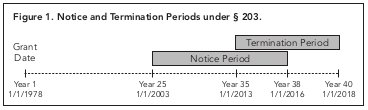

Under § 203, a notice of termination of a grant executed on or after January 1, 1978, may be given as early as 10 years prior to the start of the five-year window following the end of year 35 during which the termination becomes effective, but must be given no later than two years before the five-year window closes. In other words, the termination notice must be served 25–38 years after execution of the grant.17 For example, if an author’s grant was executed on January 1, 1978, the five-year termination window would begin on January 1, 2013, and run until January 1, 2018, and the period for serving the notice of termination would begin on January 1, 2003 (25 years after the grant) and end on January 1, 2016 (38 years after the grant).

(See fig. 1.)

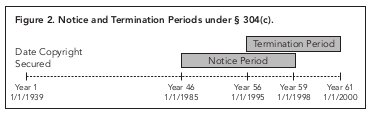

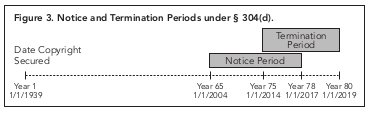

Similarly, under § 304, the termination must take effect during the five-year termination window; however, rather than starting after year 35, it follows the end of year 56 (or beginning on January 1, 1978, whichever is later) under subsection (c), or the end of year 75 under subsection (d). Also similar to § 203, under § 304, the notice can be given as early as 10 years prior to the start of the five-year window (i.e., 46 years from the date on which the copyright was originally secured under § 304(c), or 65 years under § 304(d)), but no later than two years before the five-year window ends.18

For example, under § 304(c), if the copyright was originally secured on January 1, 1939, the original five-year termination window would have begun on January 1, 1995, and run until January 1, 2000, and the period for serving the notice of termination would have begun on January 1, 1985 (46 years after the copyright was secured) and ended on January 1, 1998 (59 years after the copyright was secured). (See fig. 2.)

However, under § 304(d), presuming that the author or owner of the termination rights had not previously exercised such rights under § 304(c), the termination rights would have expired before October 27, 1998 (i.e., the effective date of the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act). Thus, they would have an additional five-year termination window that would begin on January 1, 2014, and run until January 1, 2019. The period for serving the notice of termination under this additional period would begin on January 1, 2004 (65 years after the copyright was secured) and end on January 1, 2017 (78 years after the copyright was secured). (See fig. 3.)

Notice Requirements

The requirements relating to the actual notices of termination under §§ 203 and 304(c) and (d) are also very similar for the most part. While there are some differences regarding the persons who must sign the notice, both sections require that the termination be effected by serving an advance notice in writing upon the grantee or the grantee’s successor-in-title stating the effective date of the termination, which must fall within the five-year termination window.19 Both sections also require that a copy of the notice be recorded in the Copyright Office before the effective date of termination.20 Finally, both sections provide that the notice “shall comply, in form, content, and manner of service, with requirements that the Register of Copyrights shall prescribe by regulation.”21

The requirements prescribed by the register of copyrights are set forth in 37 C.F.R. § 201.10(b)(1) and (2), and include, but are not limited to: (1) a statement that the termination is made under § 203 or under § 304(c) or (d); (2) the name of each grantee whose rights are being terminated, or the grantee’s successor-in-title, and each address at which service of the notice is being made; (3) a brief statement reasonably identifying the grant to which the notice of termination applies; and (4) the effective date of termination.

THE “TERMINATION GAP” DILEMMA

The Problem with Grants of “Gap Works”

The “termination gap” dilemma refers to “gap works,” which are works for which transfers were made by an agreement executed before January 1, 1978, but that were not created until after January 1, 1978 (the effective date of the Act). These works literally fall within a “gap” between the two sections by which an author or heir may terminate a copyright transfer (§§ 203 and 304(c)–(d)), and unfortunately leave open the question as to whether or not termination rights apply to such works.

Due to the fact that § 304(c) and (d) only allow for the termination of a grant in connection with “any copyright subsisting in either its first or renewal term on January 1, 1978,”22 those subsections would be inapplicable to “gap works” on their face, because the copyrights for those works (i.e., those works created after January 1, 1978) would obviously not be subsisting as of January 1, 1978. However, the applicability of § 203 to such works is also unclear. Due to the fact that § 203 only allows for the termination of a grant “executed by the author on or after January 1, 1978,”23 it would also arguably be inapplicable to any grant made by an agreement entered into before January 1, 1978.24

Copyright Office Addresses the “Termination Gap” Dilemma

In March 2010, recognizing this dilemma, the Copyright Office posted a notice of inquiry requesting comments regarding how best to handle “gap works.” In response thereto, the Copyright Office received numerous comments, and in December 2010 issued a detailed analysis of gap grants under the termination provisions of Title 17. In its analysis, the Copyright Office summarized the nature of the problem, in particular whether or not § 203 should apply to gap works, as “a very technical question,” namely: “Is it possible for an author to execute a grant prior to creating the work of authorship?”25

The Copyright Office answered this question in the negative, taking the position that in the case of a grant signed before January 1, 1978, regarding rights in a work not created until January 1, 1978, or later, such grant cannot be “executed” until the work exists.26 Accordingly, the Copyright Office amended 37 C.F.R. § 201.10 to allow termination notices for “gap works” to be accepted and recorded with the Copyright Office.

The amendment added a new paragraph (f)(5), which reads:

In any case where an author agreed, prior to January 1, 1978, to a grant of a transfer or license of rights in a work that was not created until on or after January 1, 1978, a notice of termination of a grant under section 203 of title 17 may be recorded if it recites, as the date of execution, the date on which the work was created.27

While the Copyright Office should be applauded for its proactive attempts to address the gap dilemma, its efforts and subsequent amendment to its notice requirements do not in any way act as a substitute or remove the need for this issue to be addressed by Congress and/or the courts. The Copyright Office acknowledged the need for further resolution by noting that its “recordation of notices of termination of Gap Grants is without prejudice to how a court might ultimately rule on whether any particular document qualifies as a notice of termination within the scope of section 203, consistent with longstanding practices for all notices of termination recorded by the Office.”28 Further, the Copyright Office stated that any dispute over the validity of such a notice of termination “should be settled in the courts (or in Congress, if Congress accepts the Office’s suggestion to enact legislation that will clarify the status of Gap Grants).”29

Moreover, as correctly pointed out by attorneys Michael Perlstein, Bill Gable, and Kenneth D. Freundlich in their comment to the Copyright Office regarding the notice of proposed rulemaking, the Copyright Office’s conclusion that “execution of the grant” in § 203 means the post-1977 date when a work is created, while correct, on its own is “likely to generate litigation.”30 The reason for this is because without any corresponding statutory framework setting forth how the date of execution of the grant (i.e., the date of creation) should be determined and established, the Copyright Office’s amendment raises and creates many questions about what an author (or author’s heirs) must show to prove a date of creation.

The problem, as explained by Perlstein, Gable, and Freundlich, is that “neither authors nor their grantees (e.g. publishing companies) were ever on notice that they needed to retain documents evidencing date of creation (as distinguished from date of delivery, for example), and that even if such documents may once have existed neither party often will have preserved them.”31 The Copyright Office’s “requirement of identifying a date of creation 35–40 years after the fact is unrealistic and likely to generate litigation,”32 which is something that these regulations should seek to avoid.

Perlstein, Gable, and Freundlich went on to propose a series of guidelines for possible future legislation to set forth other bases to determine the date of execution of a grant under § 203, which, as they describe, are “author-friendly [and] consistent with the legislative and judicial intent that authors and their heirs benefit from the termination statutes.”33 The guidelines are an “order of priority” of documents and other means to be used to determine the date of execution of the grant, including, but not limited to: (1) “written documentation signed by the author, e.g. a short form instrument of transfer or single song agreement . . . or note or memorandum of some sort, with a date post-1977”; and (2) “the date of publication as set forth on the Certification of Registration.”34 Whether or not Congress adopts any or all of these proposed guidelines or other similar guidelines, it is clear that a more practical framework and statutory clarity are necessary.

CONCLUSION

Congress’s intent in enacting the Copyright Act was clearly to give authors or their heirs a second opportunity to share in the economic success of their works, and as such, it seems extremely unlikely that Congress intended to exempt “gap works” from possible termination. However, while the Copyright Office has concluded that “the reasonable interpretation of Gap Grants is that they are terminable under section 203 as it is currently codified,”35 until there is statutory clarity on this issue from Congress, it is very likely that Congress’s intent to ensure that authors have enforceable termination rights will be undermined.

As stated by the Copyright Office, “Lack of clarity will likely result in costly delays, the prospect of inconsistent or unfavorable court decisions, or a state of play where termination rights are left unexercised . . . .”36 Hopefully Congress will take action in the immediate future to provide clarity on this issue and preserve what was clearly meant to be a legislative means to protect authors and their works, and not to drown them in unnecessary and expensive litigation.

ENDNOTES

1. See 17 U.S.C. §§ 203, 304(c)–(d).

2. See Korman v. HBC Fla., Inc., 182 F.3d 1291, 1296 (11th Cir. 1999); H.R.Rep. No. 94-1476, at 124 (1976).

3. H.R. Rep. No. 94-1476, at 124.

4. See Korman, 182 F.3d at 1296.

5. 17 U.S.C. § 203(a).

6. Id. § 203(a)(3).

7. Id. § 304(c).

8. Id. § 304(c)(3). The reason for the 56-year measure, as opposed to the 35-year measure for grants made after January 1, 1978, is based on the fact that 56 years constitutes the maximum term of protection for all works under the 1909 Copyright Act, and the termination of such grants permits the author to recapture ownership in the work during the 19-year additional period that was added to the renewal term by the 1976 revision of the Copyright Act.

9. Compare id. § 203(a)(3), with id. § 304(c)(3).

10. See id. § 304(d).

11. Id. § 304(d)(2).

12. Id. § 304(d)(1).

13. Id. §§ 203(a)(5), 304(c)(5).

14. Id. §§ 203(a), 304(c).

15. A termination of rights is only applicable within the geographic limits of the United States. Thus, an author is precluded from terminating rights based upon foreign copyright laws, and a grant of copyright “throughout the world” is terminable only with respect to uses within the United States. Id. § 203(b)(5).

16. A derivative work prepared under the authority of the grant before suchgrant is terminated may continue to be utilized under the terms of the grant after its termination. Id. § 203(b)(1).

17. Id. § 203(a)(4)(A).

18. Id. § 304(c)(4)(A), (d)(2).

19. Id. §§ 203(a)(4)(A), 304(c)(4)(A).

20. Id. Notices of termination should be submitted to the address specifiedin 37 C.F.R. § 201.1(b)(2) (i.e., Copyright Office, Notices of Termination, P.O. Box 71537, Washington, DC 20024-1537).

21. 17 U.S.C. §§ 203(a)(4)(B), 304(c)(4)(B).

22. Id. § 304(c).

23. Id. § 203(a).

24. See Jake Shafer, The Gap Years, L.A. Law. (Nov. 2011), at 36, 38.

25. U.S. Copyright Office, Analysis of Gap Grants under the Termi-nation Provisions of Title 17, at ii (2010), available at http://www.copyright.gov/reports/gap-grant-analysis.pdf [hereinafter Analysis of Gap Grants].

26. Id. at 1.

27. 37 C.F.R. § 201.10(f)(5).

28. Gap in Termination Provisions, 76 Fed. Reg. 32,316, 32,320 (June 6,2011), available at http://www.copyright.gov/fedreg/2011/76fr32316.pdf.

29. Id.

30. Letter from Michael Perlstein, Bill Gable & Kenneth D. Freundlich, toMaria Pallente, Acting Register of Copyrights (Jan. 24, 2011), http://www.copyright.gov/docs/termination/comments/2011/freundlich-law.pdf.

31. Id.

32. Id.

33. Id. (citing Mills Music, Inc. v. Snyder, 469 U.S. 153 (1985); Korman v. HBC Fla., Inc., 182 F.3d 1291 (11th Cir. 1999)).

34. Id.

35. Analysis of Gap Grants, supra note 25, at 7.

36. Id.